When anyone thinks of modern gothic horror and fantasy, you inevitably encounter ideas shaped and influenced by Kentaro Miura–creator of Berserk. From fantastical creatures with strangely undulating shapes and contorted features, to sprawling scenic backgrounds depicting the harshness and inevitability of nature’s cycle, Miura was able to pen and ink a one-of-a-kind story that engrossed countless fans across the world. News of his passing officially broke late Thursday evening in North America, May 19. He died of an acute aortic dissection, otherwise known as a type of rupture in the largest heart valve. No one can be sure what led to it happening–but there’s been an outpouring of grief at the loss, indignation at the working conditions that artists in the manga and anime industry are subjected to, and celebration of the cultural impact he left for us.

Berserk itself may not have been on Toonami, but its influence can be felt in numerous works. Koyoharu Gotouge of Demon Slayer cited it as one of their primary influences. While demons themselves are not as monstrous and deformed as they are in Berserk, they display the emotional vulnerability of humanity just as significantly, especially when pitted against temptations of the id in moments of desperation. Fire Force’s Atsushi Ohkubo mentioned how the series was an invaluable part of his upbringing and how he even went to see Miura at an event in Shibuya! Ohkubo’s previous work, Soul Eater, practically oozed Gothic fantasy in its character designs. And in Fire Force, Infernals initially being humans that the Church exploited, feels eerily similar to how Apostles are chosen (and manipulated) by the God Hand. Although not as gruesome, Black Clover has some more obvious homages–like William Vangeance being a masked charismatic knight from humble beginnings like Griffith, and Asta wielding a giant sword and getting a dark transformation that feels hellish in nature. Tabata himself even stated in a French interview that as a fantasy story, he wanted to make Black Clover like Berserk, but for shōnen manga! While the Berserk TV series did not air on Toonami, I’d be remiss if we didn’t discuss Berserk’s legacy. It’s clear that many titles would be vastly different or not exist at all.

What makes Berserk so special? Many peoples’ first impressions are a gritty, dark action series about rage–a power fantasy about a macho man who shoots first and asks questions later. Which is so far away from the truth it isn’t funny. The gritty male power fantasy falls apart once we learn that the source of his strength comes from a rage that stems out of self-defense. He lashes out to protect himself, refusing to form bonds with others after getting betrayed the one time he finally opened up and accepted others into his life. It’s a story about vulnerability. Miura was once interviewed and got the offhanded comparison that his series is close to shojo manga. It’s a story that strongly prioritizes the depiction of emotions in a powerful way, instead of manga written “for men,” which–according to Miura–tends to be more consciously written to sell rather than express any specific thing. The unique thing about Berserk is that the longer the story unravels, the more nuanced the emotions depicted become. Even before the betrayal, Guts (the main character) is a victim of sexual abuse who tries to hide his pain from others to avoid more of it. In volume one, Godo, the man who forges the massive sword, Dragon Slayer, says, “Hate is a place where one who can’t stand sadness goes.” From the very beginning, it’s clear from hindsight that the emotional journey Guts is going through will run further than only surface deep.

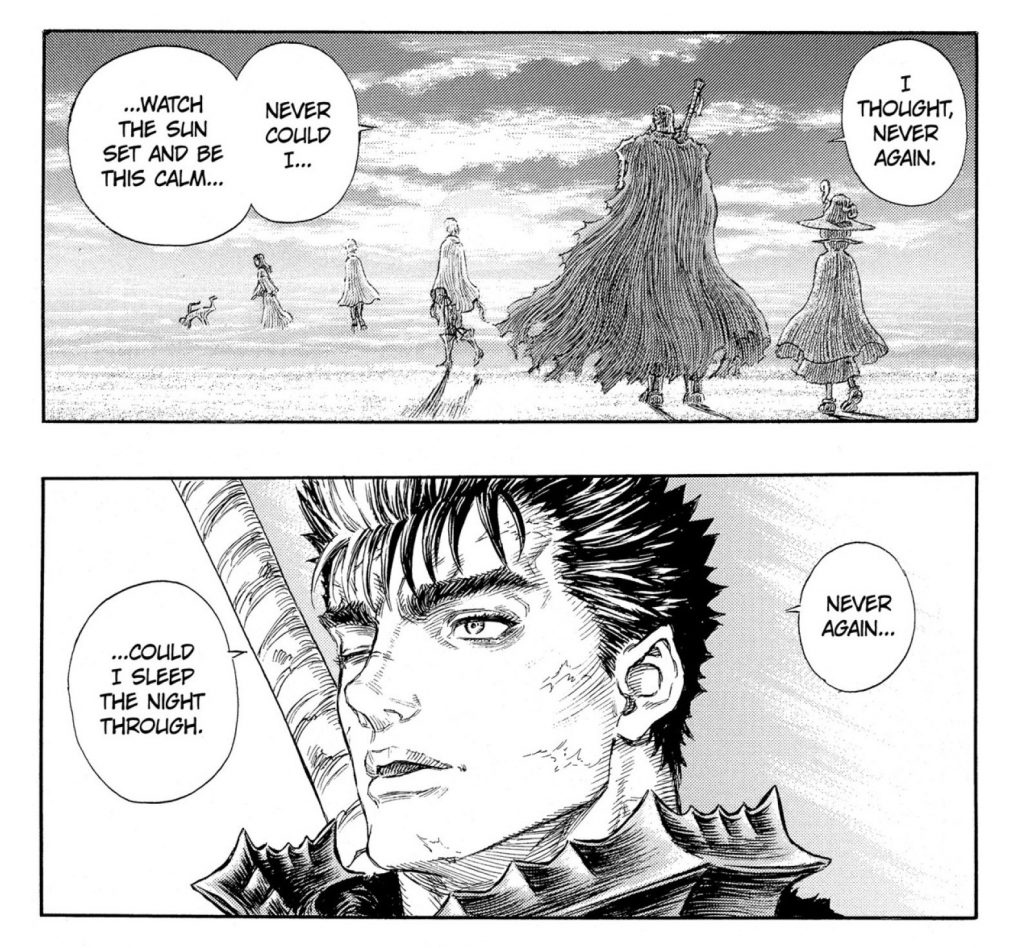

There are tons of other aspects that appeal to readers, such as the themes of causality and destiny, how far free will truly extends, because of it, and what it means to struggle against that. At the core of that very struggle, Guts is living through the idea of hope. Rage and hatred can only push a man so far. Still, thanks to the people he meets later on–Puck, Casca, Isidro, Farnese, Serpico, and Schierke–he’s able to maintain his humanity, feel other emotions, and gradually heal from the trauma. Some of the most breathtaking and artistically fulfilling pieces to look at in this comic come from moments of introspection and wavering emotions, where characters feel the extent of the life they’re living and the breadth of love and care shared by their comrades. The same feelings of wanting to trust and share in each others’ vulnerabilities, even if they were taken advantage of when they were more naive, are what saturates the bleakness of “destiny,” “causality,” and the inevitable–with hope, reassurance, and resolve to continue. It’s very metal to struggle against destiny, but even more so with the backing of your friends (TL note: Nakama can mean friend or comrade) by your side.

Besides the intricacies of its complex character relationships, Berserk is very good at being a comic, in general. There’s no end to the imaginative creature designs (Potentially NSFW) that flood the pages in expansive spread pages, and countless homages to various pages and panels have bled into the cultural zeitgeist. For every Spongebob screencap that turns into a Twitter meme, there was a Berserk reference somewhere else. Being quotable or easy to remember doesn’t explicitly make something good but is a sign of being in tune with what people care about in the media we consume. As par for the course of a gargantuan cultural pillar, there must also be plenty of contention in the marketplace of ideas.

Berserk itself isn’t an unblemished piece of perfection. Part of what continually adds to the appeal of reading such a long-running series is seeing character development from all members of its cast. Unfortunately, one of the more significant caveats is its portrayal of gratuitous sexual violence. On two specific occasions, it gets morbidly graphic and disturbing to the point of grave concern. I don’t want to handwave it, saying that Miura is a product of growing up and publishing in the 80s. On multiple occasions before this, Miura demonstrated his capacity for depicting emotional and sexual trauma without getting morbidly graphic, considering Guts’ backstory. The dehumanization that comes from that level of desecration and borderline contempt for the female body is taxing and frustrating, perhaps not for the intended reasons. The only reason I can look past it now, so many years later, is because of the story’s scope and being able to see the journey of one particular woman who suffered that indelible trauma. That character is Berserk’s primary female lead, Casca.

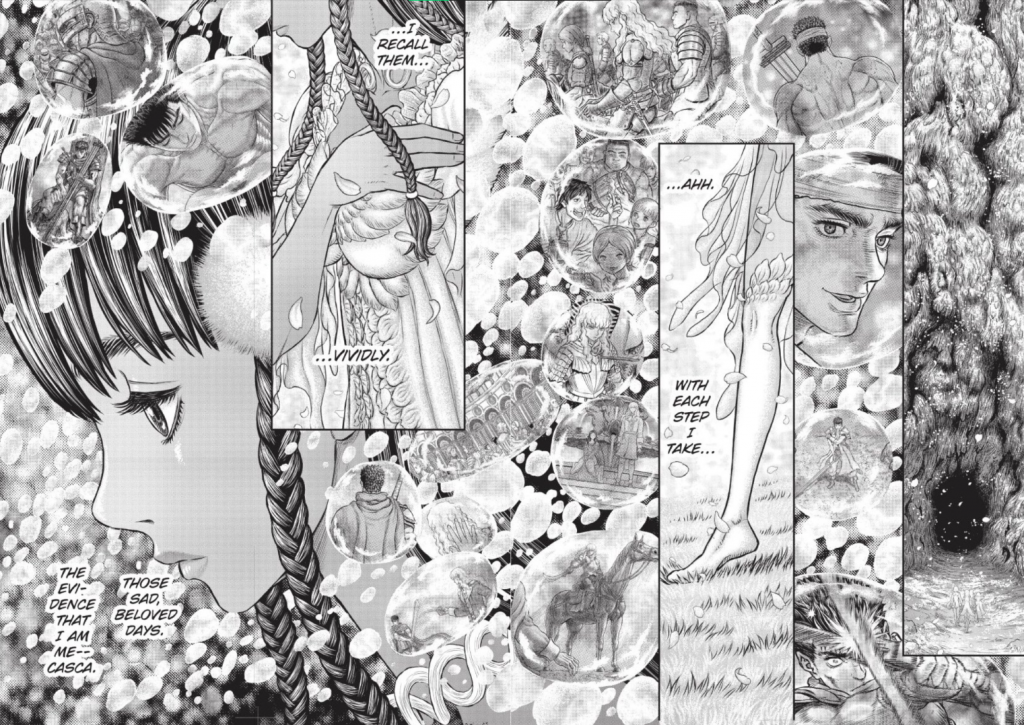

The treatment of Casca will define how a reader chooses to engage with the series, if at all. She is decisively my favorite character in the entire series. The vast majority of her characterization comes from the Golden Age Arc, the patch of the story adapted multiple times in animated and video game format. After the events that conclude the Golden Age, her traumatic experience has left her mentally and emotionally scarred to the point of amnesia, subconsciously reverting to an infantile state to survive. It feels so messy. The use of sexual assault to highlight women’s pain in medieval settings is frustratingly pervasive in media. But there’s something more to Casca’s depiction in the story. She is the focus of the journey. After Guts reencounters her and dedicates his self-sacrifice to bring her stability, Casca becomes both a recipient of empathy and the lifeline of everyone’s humanity. Never once is she blamed for her trauma. Not a single time is she devalued by her comrades for suffering in her current state. She is living proof that the aloof and rough Guts is not simply a hateful misanthrope. Part of self-sacrifice is the idea that someone does not matter. With someone to protect, the value of one’s own life also swells, and that in turn also makes Guts less eager to die. Casca also knows that. For a more nuanced and deeper dive into Casca as a character, I highly recommend reading Jackson P. Brown’s editorial article for Anime Feminist.

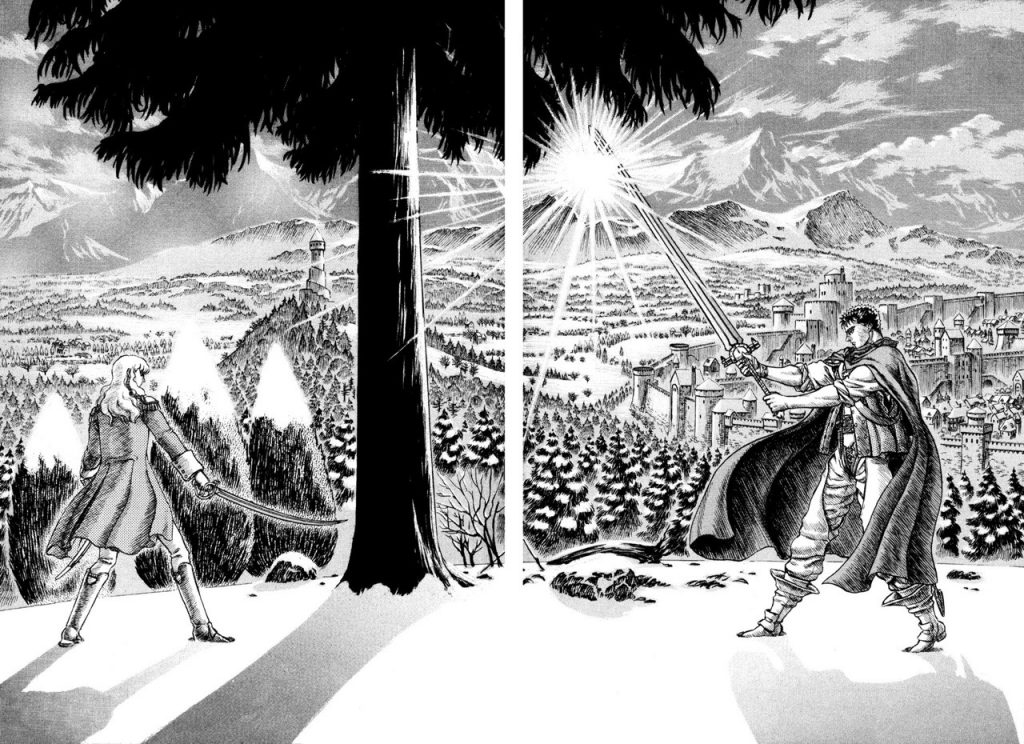

But Berserk isn’t solely about one central figure (either Guts or Casca). As a character piece, I’m enthralled with how the relationship between Guts, Casca, and Griffith (and practically every character) shapes the scope and depth of the series. I used to be soured on the Golden Age Arc, from how much attention it received compared to all of the other story arcs that weren’t animated. But with some time away from it, I fully understand how pivotal and vital it is. The Golden Age Arc works as a prologue, as its own standalone story, and as a biblical fable that explains how the world works. The earlier mentioned themes of causality and destiny coalesce in part due to the natures and desires of our leading trio. It hit me while watching the animated movie trilogy. Still, the events that transpired could not have happened if anyone else because everyone’s actions are so firmly rooted in their personalities, which are influenced uniquely by their pasts. Griffith and Guts had an incredibly close bond but fundamentally had different desires. Griffith was willing to submit himself to the kind of trauma and denigration that shattered Guts emotionally as a child for the sake of his dream. Without his goal, Guts left the Band of the Hawk to find it. Guts wanted to stand beside Griffith as an equal. Casca, who didn’t have her own ambition, opted to bring Griffith’s to fruition. Without Guts’ presence, Griffith was unable to keep up the momentum he had built, and the resentment, regret, and refusal to abandon his dream is what manifested in the Eclipse. The ebb and wane of human desire and vulnerability is the glue that holds all of the intricate plot and character development together. What makes this series feel timeless, regardless of the setting, is the fact that at its base, the relationships that form the core of the tragedies and miracles in the story exist everywhere. The way everyone was characterized, it felt as if there was no other possible way that all of these events could have unfolded! It gobsmacks me whenever I think about it! Everyone is so human, even after the Golden Age.

While I may feel the Golden Age Arc is Berserk’s most memorable storyline, the long-running epic has different parts that can engulf readers into the world that Guts inhabits. It’s because of how invested the audience is with Berserk’s characters that every arc becomes enthralling. Most notably where the story is currently, Casca has regained her psyche, but meeting Guts face to face will mean confronting her trauma in a way she hasn’t chosen for herself. Memories of the Eclipse resurface, and a visceral fear prevents her from even looking at Guts’ face. The freedom of choice exists for her “now,” in that she can choose to let time heal her wounds or face and remember her trauma directly to acknowledge and face the person she loves. I don’t think that’s a fair choice at all or tactful in the way it’s being presented. However, I appreciate the acknowledgement from the party that what Casca chooses is entirely up to her. Guts’ choice to restore her mental state was solely his–an arguably selfish decision to pry a woman from her method of coping and processing severe trauma. It’s very messy from an emotional perspective, but understandable how both parties feel about and want to process their wounds. But this type of development is inherently human at its core. You don’t get these types of emotions or human interactions in other major projects, or at least not in the same breath at how Berserk has handled it. And while some may argue that this property didn’t handle it the best, the chaotic nature Miura imbued it with is what makes this comic feel uniquely mesmerizing to read.

These feelings are why I’m perfectly fine with not getting a more concrete resolution to this story thread. The sojourn to “restore” Casca is complete. Her rapport and bonds with the rest of Guts’ party, before and after the event, have been addressed. Her actual trauma is still not fully healed–which means sense; it’s not an issue that can be solved instantly with magic. The emotional weight of the entire journey holds true to the human experience. Through these developments, Casca’s role in the narrative, and her symbolic role as an object of empathy and infantilization, does not supersede her character’s full growth. People are free to think and feel otherwise, though, because personal experiences will surely color the effects these events have on readers.

Fans across the world have had their share of heated debates over how the story was handled over time. As a voracious, opinionated fan of the series, I too have my fair share of takes about Berserk as a whole, both in manga and anime format. Because with it being one of the most recognizable series ever, there are many issues others have when talking about any format of Berserk. Starting off with the more recent anime series.

- Shin Itagaki did nothing wrong–if you call the 2016 anime “lazy” you have no awareness about how the industry works. As a director and storyboarder, he did more than a competent job of making do with his resources and visually exploring how to use CG for action and introspective scenes.

- Even if an adaptation can’t visually match its source material in execution, it doesn’t make the source itself or the actual franchise any lesser. The manga still exists. Go buy it if you don’t already own it!

- Every single adaptation has been a success, regardless of how vocally fans think otherwise. Every single time Berserk has been animated, print sales for the manga have skyrocketed even further. Word of mouth alone has proven Berserk to be one of the most successful comic franchises ever–it is still one of the best selling graphic novels period, regardless of how little promotion it receives in North America.

- For how successful this series is, it’s almost unfathomable how hellish it used to be to collect volume by volume. Dark Horse as a publisher is inconsistent with keeping up with print-demand, and couldn’t even promote the actual release of their officially licensed light novel spinoff, The Flame Dragon Knight.

- The music alone is plenty of reason to give each anime adaptation a shot if you love the source material. Every animated adaptation has had Susumu Hirasawa attributed as composer, best known for his musical work alongside Satoshi Kon’s productions such as Millenium Actress, Paprika, and Paranoia Agent.

- The frequent hiatuses between chapters were necessary, and not nearly as long as they should have been. Overwork is one of the major causes of death in both the anime and manga industry. Miura’s noted cause of death can be exacerbated and influenced by genetics, or by high blood pressure. Hiromi Tsuru, the lauded and beloved voice actress for Bulma Briefs in the majority of the Dragon Ball franchise, as well as Meryl Stryfe in Trigun and Ukyo Kuonji in Ranma ½, died of the same causes, at age 57, back in 2017. There is no confirmation to what could have led to either of their physical conditions to that point, but it’s common knowledge that many manga artists sleep as little as 2-4 hours a night, and take virtually no holidays off in order to meet deadlines.

- It’s okay that Berserk may never be finished. At the current point in the narrative, the larger questions surrounding the world and Guts’ revenge feel petty and irrelevant to the emotional state of Guts and Casca’s relationship. Having the potential for closure is more than enough, because what becomes of their relationship is up to the discretion of both characters. The beauty of fiction lies in the reader’s interpretation! I’m not telling you to read derivative fan works, but outlets like those are incredibly useful and worth exploring for both creators and readers alike.

- It’s also okay that even with all its influence, merits, and pervasive touch on modern pop culture, there are others that won’t like or care about the series. Toxicity is the antithesis to everything the narrative was trying to convey. Instead of “An eye for an eye,” by opening up and re-learning how to trust and rely on others, Guts was learning how to “Live and let go” in order to save Casca.

What hurts is how inevitably the conversation about manga authors stepping away to take care of their health will once again be in the forefront. I say this hurts, mostly because we still are having this conversation. Due to the irregular publishing of Berserk, the questions about working conditions as well as the overall health of the author can lead some into takes that I want no part in accepting. In order to truly appreciate what was given to fans, a serious re-evaluation is needed of the strenuous working conditions countless creatives place themselves under–either willingly or by outside forces. Yoshihiro Togashi, creator of beloved Toonami favorites Yu Yu Hakusho and Hunter x Hunter, is another well-known artist, known in the public eye for his serious health conditions–stemming from the latter half of his serialization of Yu Yu Hakusho–which forced him to adopt an irregular publishing schedule in order to not aggravate his condition. Even when he was being published weekly, his candid weekly comments in the magazine about working through pain were shocking and frustrating. I don’t want content at the risk of losing the creator behind it! Unfortunately, some fans might not feel the same–or at least, not realize that’s how they come off as selfish or misguided. All that I ask, as a person who enjoys creating content as much as I consume it, is to have some empathy. The unfortunate reality is that countless mangaka have passed away due to overwork, including the “Godfather” and the “King” of manga, Osamu Tezuka (Astro Boy, Black Jack) and Shotaro Ishinomori (Cyborg 009, Kamen Rider). The value of a human life is immeasurable. It’s even harder to fathom when it’s someone you care about, yet have never met, like a hero or celebrity. Kentaro Miura was undoubtedly one such presence for many of us. Just as Guts gradually shed his borderline suicidal self-sacrificial tendencies, in order to live and protect Casca, we as fans should do what we can to improve as people and effect change that save the lives of people we care about–whether it’s improving working conditions for creators we love, or being more educated and equipped to improve the life of a relative or friend.

Kentaro Miura’s legacy as an artist is inarguably unavoidable. For a man who came up with such a tragic and sad story, it’s clear that his love for art and the human condition also shaped the core of that tale. He didn’t shy away from elevating the works of others that he also enjoyed, like Chica Umino, creator of Honey & Clover and March Comes In Like a Lion, to rivals in other publications like Kodansha’s George Morikawa of Hajime no Ippo (The Fighting!!), or even Hakusensha’s Mizuho Kusanagi with Yona of the Dawn. As a pillar of culture, it’s only fitting to acknowledge your contemporaries, who no doubt had equally inspired him as he did for others. It is actions like these that humble a (mostly) otherwise unknowable presence. Being able to uplift others is a sign of empathy and appreciation for what others can do. Much like Guts, and the actual art in the story, Miura is a person who grew over time. As the content gradually shifted in tone, it’s clear that the years of life experience directly influenced the story itself and how Miura chose to interact with others. He published two other unique works, Gigantomachia and Duranki, alongside his irregular updates to Berserk. The artistry and imagination on display showed the world just how much more he had to give. His loss will be felt everywhere, but that doesn’t mean we won’t have what he gave to us. Instead of lamenting what we will never get from him, I believe we should celebrate what exists already.

Marion is a staff writer at Toonami Faithful. Feel free to follow them on Twitter. All of their other writing and podcasting projects can be found here as well.